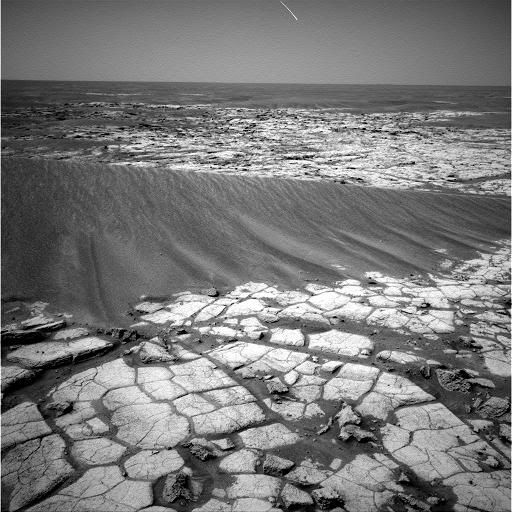

why go to spaceBack in February I

laid out the case for why we should go to the moon. I had basically stated that there were certain resources available on the moon, and that the things learned while living and working there would be applied to living and working anywhere in the solar system. However, I feel that the arguments I presented there only scratched the surface of a larger issue.

That is, why bother at all? There are resources available on the earth, and lots of infrastructure here already. What is the point of going into space?

First of all, the earth is finite. There is only a limited amount of natural resources available here. Whether it is oil or nickel or tungsten or elbow room, eventually we will have extracted all of some resource that it is economical to extract. Let's take energy as an example.

Right now, there are six main sources of energy. Three of them - oil, coal, and uranium - are energy storage mediums: their energy was stored in their chemical bonds (or in the case of uranium, in the forces binding the nuclei together) hundreds of millions to billions of years ago. The other three - direct solar power and its derivatives, wind and hydroelectric power - are the transfer of energy from sunlight into electricity. The first three are limited in quantity, and as we discover and extract and utilize those sources, the supply dwindles. At some point, the remaining supply will be so hard to discover and extract that it will be impossible to make a profit doing so. If we somehow manage to keep going extracting those sources long after they become uneconomical, then the supply will eventually dwindle to nothing.

However, before the supply of those three runs out, the other three become relatively more economical to pursue. The problem with solar, wind, and hydroelectric power is that each requires a considerable footprint, and each has problems and environmental effects of its own. Photovoltaic panels require harsh chemicals for their production, earth's atmosphere filters out about a third of the sunlight, and on average any given plot of land is only sunlit half the time, with a high angle of incidence in the mornings and evenings. Wind farms, if done on a very large scale, would interfere with airflow patterns around the world. And hydroelectric power requires huge areas of land to be flooded.

And yet, worldwide energy consumption increases every year. This is a situation that obviously cannot continue indefinitely.

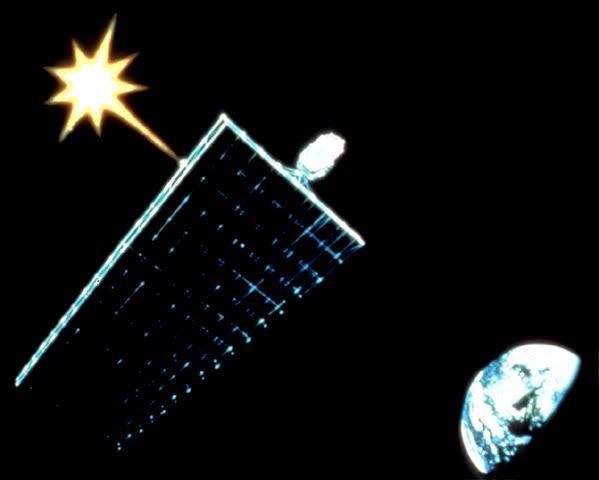

This is where utilization of space becomes the solution. In space, as long as an object is not in the shadow of another object, the sun is shining all the time. There is no atmospheric filtration, and a solar collector can be aimed directly at the sun continuously. Space-based solar power is thus able to collect all of the available light in a given cross-sectional area. And in zero gee, such a cross-sectional area can be built arbitrarily large. In the shadow of such a collector, the temperature is equal to the ambient temperature of the universe, about 3 degrees Kelvin. With that kind of temperature at the radiative end, a heat engine becomes enormously efficient, approaching unity. Therefore, a space-based solar power collection system wouldn't have to be made up of a huge array of photovoltaic panels, but instead could be a simple collector (a giant parabolic mirror) focusing light on a heat exchanger. A working fluid moving from the heat exchanger to a radiator in the shadow of the collector would drive a generator, producing electrical power.

That power would then be beamed to the earth in the form of microwaves (which pass completely through the earth's atmosphere) to large rectennae on the ground. A rectenna is basically just an array of wires and diodes suspended above the ground, and the land underneath such a device could still be used for agriculture. The rectenna would be hooked directly into the existing power grid.

If the solar power satellite is in a geosyncronous orbit, then it can be sunlit for the 99% of the time that it is not in the earth's shadow, and beam power to a rectenna directly below it on the ground. If the solar power satellite is in a halo orbit around the Earth-Sun L1 point, then it would be continuously generating power to beam to the earth.

Such solar power satellites have the potential to replace many of our conventional energy sources, and would provide the power necessary to produce new energy storage media such as Hydrogen or methane out of raw materials (carbon dioxide and water). So, not only would such a system replace the heavily-polluting coal-fired power plants, it would also actively reduce the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere, turning it into energy-storing methane. Environmentalists should thus embrace such an idea wholeheartedly.

These satellites would be huge. Let's run through some quick calculations. If the operating temperature at the heat exchanger is 900 degrees Kelvin, and the background temperature in the shadow is 3 degrees Kelvin, then the

maximum efficiency for the heat engine I described above would be (1 - (3/900)) or about 99.67% efficient. Then there would be losses in the conversion from mechanical energy to electrical, and again from conversion from electrical to microwave, transmission losses for the microwave beam, and finally energy losses in the last conversion from microwave to electrical at the rectenna. Each of these losses would lower the efficiency of the power transmission. For a quick-and-dirty calculation, let's assume that 50% of the energy collected is lost by the time it gets to the grid (although I expect that the losses would be much less than that).

The amount of sunlight received at Earth's orbit is about 1360 Watts per meter squared, and at a 50% efficiency there would be 680 watts delivered per square meter of collector. Today's

441 commercial nuclear power plants produce 368 Gigawatts for an average of about 835 megawatts per nuclear reactor. That 835 megawatts works out to about 1.25 million square meters for a 50% efficient solar collector in orbit, or a square collector about 1108 meters (a little over 2/3 of a mile) on a side. Put another way, a 50% efficient solar collector that is a square 23.25 km (14.5 miles) on a side would equal the power production of all the nuclear reactors on earth, put together. And the vast majority of the area of such a collector would be a simple reflective surface, such as aluminum foil. The structural supports for such a device could be little more than inflated tubes.

Building such an enormous flimsy structure would be impossible on the earth, but in orbit it would be possible. And more than one such structure could be built, or even much bigger structures. These solar power satellites would thus take over the power production that we presently rely upon coal and nuclear power to provide, and could provide the energy necessary to produce methane or hydrogen economically, thus allowing the auto industry to shift away from using gasoline. Building solar power satellites like the one I describe above would enable us to finally break free from dependence on oil.

Near the top I mentioned some other things that are finite on earth... nickel, tungsten, and elbow room. I mentioned nickel and tungsten as these are elements that have many uses in industry, representative of pretty much any element you'd care to name. Eventually, like with oil, the economical supplies of these elements available on earth will run out, and extraction will no longer prove economical. And once again, space provides the solution. The material resources of the moon and asteroid belt are just out there waiting for us. Over time, as more and more industry occurs in space to provide for the construction and maintenance of solar power satellites, it will become more economical to consider extracting material from the moon and asteroids. In fact, I can see the moon being one resource that is used to facilitate the construction of the solar power satellites, as aluminum extracted from the moon could be less expensive than boosting aluminum from the earth; with the moon near the top of earth's gravity well, it doesn't take much energy to move material from the moon to earth orbit, not nearly as much as is necessary to boost it from the earth's surface.

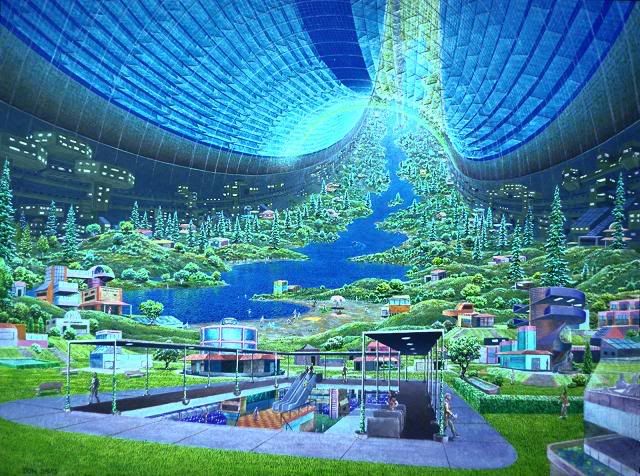

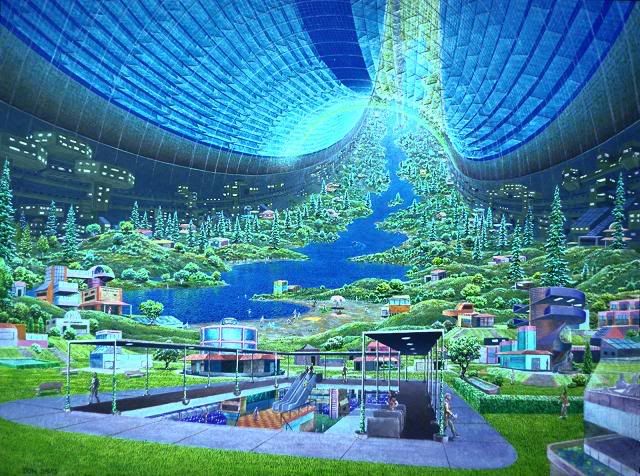

As for elbow room, well, space is big. Very big. There's lots of room up there. And, with some ingenuity and economic reasons for doing so (such as mineral extraction from the asteroids), we could be building lots of habitable space throughout the solar system. For instance: if Ceres, the largest asteroid, was dismantled and turned into space colonies, there would be enough material

just in that one asteroid to produce between 300 and 500 times the surface area of the earth. Those space stations could be enormous (some proposed designs are big enough to hold a million people), but would also be tailor-made to be equivalent to some of the most beautiful places on earth.

Not only would this alleviate problems of overpopulation on earth, but it would also spread the risks to our species out over a large volume. No longer would we be threatened by a planet-killer asteroid or comet, like the one that wiped out the dinosaurs. Our eggs would be in many baskets... and with such a huge presence in space, any potential planet-killers could possibly be mined out of existence before they pose a real threat.

So, space provides the solution to the energy shortage, a solution to shortages of raw materials, and a solution to the overpopulation of the earth. And, with space-based solar power to bootstrap everything else, it also would provide an enormous economic boost to the entire planet. Win-win-win-win.

Why go into space? We can't afford

not to.

Update: Four years later, I wrote the companion piece to this, developing space.Technorati Tags: Space,

Moon,

Asteroids,

Solar Power